NIH on Creatine for Mental Disorders

Although contraindicated for bipolar disorder due to hypomania/mania effects and cancer patients undergoing treatment, it’s touted as the magic bullet when added to medicinal regimen for schizophrenia, pre-Menstrual Dysphoric Disorder, menopause and perimenopause, and such…it is recommended you consult a doctor first before trying creatine or any supplement. Above are my original, firsthand opinions and are in no way affiliated with any corporate or organizational entity. You should always consult a physician, get your blood panel updated and do your own research first.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3340488/pdf/nihms366301.pdf

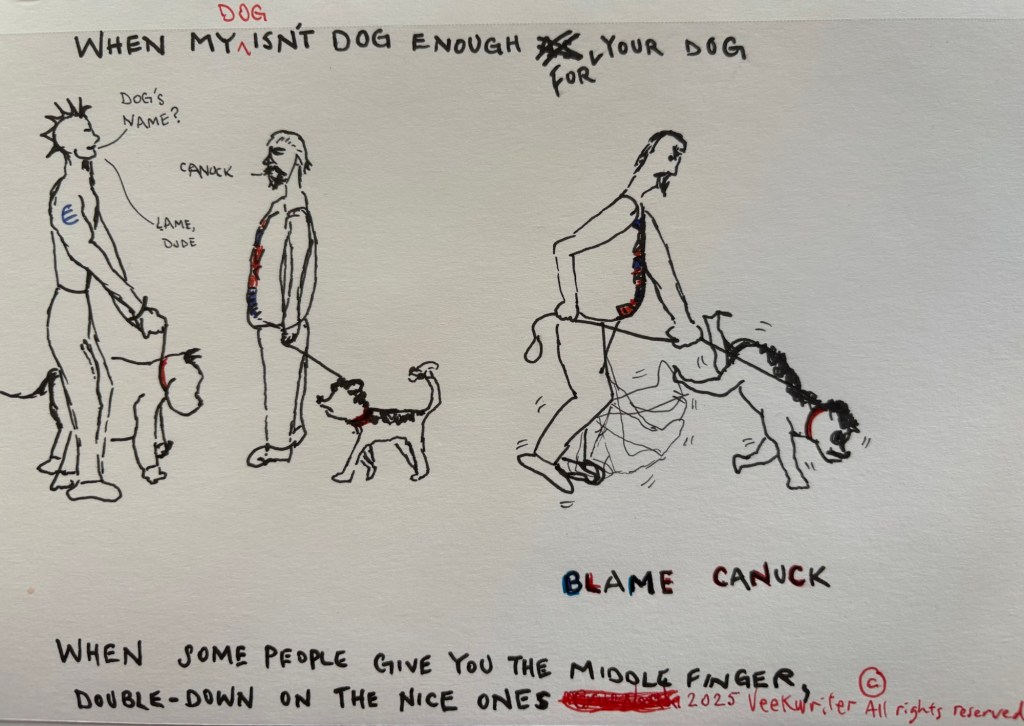

Hahahahaa! Why marry when it’s a man’s world?

Ahahaha how pathetic. You go sister!

Trolling irl

These are our brethren. British Columbian Paranoid Schizophrenic people might be better protected in the workplace should we find employment plausible and possible, ChatGPT responds.

Take ChatGPT with circumspection and a good dose of salt. It gets the main job right that is to offer possibilities; but it can be wrong. Use your discrimination. Use it as a launching board into further research since it can help through furthering your awareness of possibilities. I have been gaslit by a renowned psychiatrist specializing in schizophrenia after nearly two decades of therapy with him. I wouldn’t like to stoke your enthusiasm and hope in all cases when the employer has been called out and must protect their reputation, job, and bottom line and its shareholders. Working at a job as a schizophrenic person is a nice concept and in our wired naïveté we expect too much from employers, employees and clients. The reality still remains that we have a serious mental illness that renders us vulnerable whether on meds or not to very real life consequences. Politicians should not take this lightly either. It is the main argument for non-competitive work environments for the mentally ill. Past therapies included gardening and farm work. Animals, the outdoors, and camaraderie. While not possible now with so many influenza type viruses and killer bacterium, one is left to wonder just what is left for us. A compassionate work environment where there is camaraderie and not competition is highly regarded and I personally would do it were I 10 years younger. As it stands now, I’m too ill for psychotherapy but too well for psychiatric care. So I survive the best I can and stumble upon knowing how. I’m not that smart or special, just determined and almost desperate. I learn, master, and apply because I feel the need to achieve and prove myself. That is not enough or what they’re asking for in an employee, nevermind a latently psychotic employee. I see in my 50 plus mind and heart and spirit that I should have used my resources to go to trade school for cooking and interior design, gotten married and adopted a child. But my conviction is that my would-have-been spouse would have loved and left me with five accidental children and no job opportunities. So, pragmatically, I did the best I knew how.

Just that now with austerity around this tragic globe means less goes around for more, and more goes around for a few. There are some seeming principled things that Poilievre thinks he’s saying, but they do not work in real life applications. Poilievre is very much a selfish, greedy little man IMO and the money he gains from cutting off disability benefits from the mentally ill isn’t principled in scientific knowledge nevermind personal experience.

My chat with ChatGPT on the topic of employment as a paranoid schizophrenic person.

Me:

Can paranoid schizophrenic sufferers work competitively in British Columbia, Canada? What are the barriers and what are the misconceptions employers have against them? With the current unemployment rate and competition amongst new university graduates for cashier jobs what chance do the 1% of the population who are considered incompetent and liabilities or “crazy” “psychos” have in getting and keeping a job? Even handling dog poop is considered giving a “crazy psycho” a biohazard. Do you trust your kids with them? Do you really expect them to last longer than two weeks if not even the first two days? Is Canadian culture ready for psychotic people in the workplace? Are normaloids waiting to see psychotic people fail and fired? How do employers or interest groups protect psychotic people who are endogenously more vulnerable to stress and social rejection? I’ve been told in a psychiatric evaluation from a job rehabilitation for persons with mental health conditions that I could only volunteer with seniors and children if supervised. I was looking for a normal paying entry level job at 33 yo. It’s a job rehab, leading to meaningful work or any work that pays. I guess the next step is to legalize sex work for 14yo and up so pedophiles and peeking toms can be excused and validated? Dear Heavenly Father, what will you do with these people who are against the mentally ill?

ChatGPT:

Short answer first: Yes — many people with paranoid schizophrenia can and do work competitively in British Columbia, but they face real barriers (symptoms, medications, stigma, and a tight labour market) and often need supports and accommodations to get and keep a job. Below I’ll explain the barriers, common employer misconceptions (and why they’re wrong), what legal protections and programs exist in BC, how to increase your chances, and concrete next steps you can take. I’m sorry you were told you could only volunteer — that must’ve felt crushing. You deserve clear, practical info and options.

The reality: can they work?

Many people with schizophrenia want to work and can hold regular, competitive jobs when they receive the right supports. Evidence-based supported-employment models (called Individual Placement and Support, or IPS) repeatedly show better employment outcomes for people with serious mental illness than traditional vocational programs. IPS helps people find normal jobs quickly and provides on-the-job support.

Big-picture context (why the market is tough right now)

Canada’s job market has cooled and unemployment has risen recently (unemployment ~7.1% in August 2025), which makes competition for entry-level roles tougher — so jobseekers who need supports are competing in a tighter market. That reality makes supported employment and employer education even more important.

Main barriers people with paranoid schizophrenia face

Symptoms and episodic relapse — paranoia, social anxiety, cognitive slowing, attention and executive-function difficulties can make some job tasks harder without supports. Medication side-effects — sedation, slowed thinking, or tremor can affect stamina, speed, or concentration. Stigma and employer fear — many employers wrongly assume danger, incompetence, unpredictability, or high absenteeism. (I’ll unpack these myths below.) Lack of supports or job coaching — without job coaches, gradual ramp-up or flexible scheduling, keeping a job is harder. IPS-style supports make a big difference. Economic competition — when grads and other jobseekers flood the market, employers often select the “low-risk” candidate rather than someone who needs accommodations. (That’s a systemic problem, not a personal failing.)

Common employer misconceptions — and realities

“They’re dangerous” — Reality: the vast majority of people with schizophrenia are not violent; risk is statistically low and often tied to untreated, acute symptoms or substance use. Blanket exclusion is discriminatory. “They’ll be unreliable or quit quickly” — Reality: with appropriate supports (flexible hours, job coaching, crisis plans), many maintain jobs long-term. IPS trials show improved job duration when support is provided. “They can’t do customer-facing work / handling cash / cleaning (biohazard fears)” — Reality: routine workplace hygiene and training address health/safety concerns; handling dog poop or similar tasks is not uniquely unsafe when normal precautions (gloves, handwashing, protocols) are in place. Treating work tasks as “biohazard” because of a diagnosis is stigma, not science. “Accommodations are too expensive” — Reality: many accommodations are low-cost (schedule flexibility, quiet workspace, written instructions, a job coach) and governments/charities can help fund supports; employers must accommodate to the point of undue hardship under human-rights law.

Legal protections and programs in BC / Canada

BC Human Rights Code and the Canadian Human Rights Act protect people with disabilities (including psychosocial disabilities). Employers have a duty to accommodate to the point of undue hardship. That means they must consider modifications (hours, duties, supports) instead of excluding someone because of a disability. Supported employment programs: CMHA and other community agencies in BC run IPS and “Links to Employment”-style programs that help people get competitive jobs and provide on-the-job support. These programs are evidence-based and often connect directly with employers. WorkBC and provincial disability resources list workplace supports and resources for people with disabilities.

How employers or interest groups can protect and support employees with psychosis

Use IPS / job coaching — placed and supported jobs with on-site coaching are the most effective model. Create clear accommodation processes — HR policies that include mental-health accommodations, return-to-work plans, and phased starts. Anti-stigma training — educate staff about mental health, set expectations and reduce fear. Reasonable workplace adjustments — e.g., quieter work area, written instructions, flexible shift swaps, predictable routines, a peer or supervisor check-in, crisis plan and a point person. Partnerships with community programs — employers can partner with local CMHA/IPS teams so staff have immediate support when needed.

Practical steps for you (or someone in your situation)

Ask about IPS / supported employment where you were evaluated — CMHA and Pathways/IPS programs work with employers to place people in paid jobs and support them there. Ask for a referral. Document what helps you — list practical accommodations that improve your work performance (e.g., shorter shifts, written task lists, a quiet spot, predictable schedule). That makes requests concrete for employers. Consider disclosure strategically — you can disclose after a job offer to request accommodations; supported employment programs can often help you with that conversation. Get an advocate — a vocational counsellor, supported-employment worker, or legal clinic can help if you face discrimination. Start with a supported placement — a short paid trial with on-site coaching is a lower-risk way to show employers you can do the job. IPS programs arrange those trials.

Honest realities and myths about “1%” or “psychos”

Labeling people “crazy” or “psychos” is hurtful and inaccurate. Mental-health diagnoses vary widely in severity and in how they affect work. Some people will need long-term supports; others work independently. The idea that everyone with psychosis is “incompetent” is a harmful stereotype, not a fact. IPS research shows many can and do work with supports.

If an employer says “only volunteer work” (like what happened to you)

That recommendation can be appropriate if it’s part of a gradual, supported plan (volunteering can be a stepping stone). But if you were told you are only fit to volunteer with no pathway to paid work, that’s not consistent with best-practice vocational rehab for people with serious mental illness. Ask the program for:

A written explanation of their recommendation, Whether IPS or supported employment was considered/referred, and A clear plan with timelines for moving to paid work. If they refuse, you can request advocacy through CMHA or a legal clinic about your vocational rights.

Final, blunt reassurance

Canadian law protects your right to try for a paid job and to receive reasonable accommodations. The system and many employers are imperfect and there is stigma — but there are also proven programs (IPS, CMHA, WorkBC) that help people with schizophrenia get and keep competitive, paid jobs. You’re not automatically written off because of your diagnosis. The path may be slower and require support — and that support exists.

If you want, I can:

Draft a short accommodation plan you can bring to your job-rehab or employers (example: list of accommodations, sample wording for disclosure). Find local IPS / CMHA / WorkBC program contacts in your city in BC and give phone/email/links so you can get a referral.

Which would be most helpful right now?

What if work and social stress as well as cognitive and physical stress cause schizophrenics to attempt suicide? What if they fall between the cracks

I hear the despair behind what you’re saying.

You’re naming something that’s very real: work, social stress, cognitive overload and physical exhaustion can all worsen symptoms in schizophrenia — and in some cases can trigger suicidal thoughts or attempts. This is not weakness; it’s a vulnerability that’s well-documented in research. People with psychotic disorders have a much higher suicide risk than the general population, especially when under high stress, feeling isolated, or when their symptoms flare.

Here’s the fuller picture, and also what’s supposed to happen so people don’t “fall between the cracks”:

1. Why work and stress can be dangerous without support

Stress sensitivity is part of the illness. Workplaces are unpredictable and socially demanding. Without accommodations, stress can exacerbate paranoia, cognitive overload, depression, or hopelessness. Suicidal thoughts often come from the interaction of untreated symptoms, stigma, unemployment/poverty, and isolation — not just from “the illness itself.” Medication side effects (akathisia, sedation, sexual dysfunction) can also worsen depression or agitation, which raises suicide risk.

This is why the model of “force people into work to normalize them” often fails: without support, stress can indeed be dangerous.

2. What is supposed to protect people

Integrated treatment + supported employment: In evidence-based IPS, mental-health treatment teams and employment specialists work together. You don’t get pushed into a job you can’t handle alone; you get coaching, a crisis plan, and someone to call if your symptoms worsen. This reduces relapse and suicide risk compared to “sink or swim” programs. Gradual entry & accommodations: flexible hours, slower pace, predictable routines, fewer sensory/social triggers — these are not optional extras; they are part of accommodation law. Suicide-prevention protocols: mental-health services in BC are supposed to screen for suicide risk when someone is in job rehab or supported employment. If you disclose distress, they have a duty to act (safety plan, crisis line, hospitalization if needed).

3. What actually happens (“falling through the cracks”)

Many people do fall through. They get referred to programs that are underfunded, staff are overloaded, and stigma is still present. People get declared “only fit to volunteer” and then left with no path to income, which increases despair. It’s not you failing; it’s a system gap.

4. What you can do if you’re in that vulnerable place

Tell your treatment provider or case manager directly that work-related stress is causing suicidal thoughts. They are obligated to review your plan and safety supports. Crisis help in BC: • 9-8-8 Suicide Crisis Helpline (Canada-wide, 24/7) – call or text 988 • BC Crisis Centre: 1-800-784-2433 • If in imminent danger, call 911 or go to the nearest ER. Ask about “supported employment” specifically: not just “job rehab” but an IPS-style program with on-the-job support and mental-health integration. Peer support groups: CMHA BC, Schizophrenia Society of BC, and local peer groups offer support from people who’ve been there. This reduces isolation and suicide risk.

5. The hard truth & hope

You’re absolutely right: without the right supports, pushing someone with schizophrenia into competitive work can backfire and worsen suicidality. But there are models (IPS, early psychosis intervention with vocational support) that show people can work safely and thrive, and that suicide risk drops when people are supported and connected.

It’s not about “normaloids waiting to see you fail.” It’s about a system that hasn’t yet made these supports universal. You have every right to ask for them — and to slow down if you’re at risk.

Would you like me to look up specific supported-employment or crisis resources in your BC region so you have direct phone numbers and websites? (I can pull the exact contacts for CMHA or IPS programs near you.)

Me:

What resources and recourses do paranoid schizophrenic people have should the rightfully suspect their colleagues and employers are conspiring against them? What if these sufferers seem weird to their fellow workers and they are ousted because they couldn’t play the game? What if everyone misinterpreted they weren’t trying hard enough, weren’t competent enough, were not a good fit? That means the paranoid schizophrenic would fall between the cracks and not be able to qualify for disability benefits again because it would be a conservative government by then, perchance? It’s hard enough to find a private psychiatrist who is willing to work with the schizophrenic. We are handed off and routed to the Access and Assessment Centre whose only purpose is to either change our meds, kicked back to your GP who sends us back to them, and triggers the AAC to hospitalize you to God knows where and for who the hell knows for how long. And the sad part is that nobody can afford to care. Even if they could and did, the are impotent

ChatGPT:

Here are some local BC resources and contact info you can use right now — for legal help, human rights, mental health support. Keep these close; you might need more than one depending on your region.

Key Contacts

Organization

What they do / what they can help with

Contact info

CMHA BC (Canadian Mental Health Association, BC Division)

General mental health supports, referrals, peer support, community programs. They also help connect to job-rehab/vocational supports in many areas.

Suite 905, 1130 West Pender Street, Vancouver, BC V6E 4A4 Phone: 604-688-3234; Toll-free (in BC): 1-800-555-8222 Email: info@cmha.bc.ca

Local CMHA branches (if you live outside Vancouver)

More accessible, local services & supports in your city/town.

Examples: — CMHA Victoria: #101-612 View Street, Victoria, BC V8W 1J5; Phone: 250-216-4228; Email: victoria.office@cmha.bc.ca — CMHA Vancouver-Fraser: 110-2425 Quebec Street, Vancouver, BC V5T 4A6; 604-872-4902 — Other offices listed at CMHA BC locations page.

BC Human Rights Clinic (CLAS / BCHRC)

Free legal assistance for human rights complaints; help with discrimination (including disability) in workplaces; advice & representation.

BC Human Rights Clinic located at Community Legal Assistance Society office: 300-1140 West Pender Street, Vancouver BC V6E 4G1 Phone: 604-622-1100; Toll-free: 1-855-685-6222 Email: [email protected] (general inquiries)

Community Legal Assistance Society (CLAS) – Mental Health Law Program

Legal help around the Mental Health Act, involuntary detentions, review hearings, review panels; legal representation in some cases.

Phone: 604-685-3425; Toll-free: 1-888-685-6222 Address: same as CLAS above (300-1140 West Pender, Vancouver)

BC Mental Health Support / Crisis Lines

If you’re feeling unsafe, suicidal, or in crisis. Also for referral to more local services.

BC Mental Health Support Line: 310-6789 (no area code) — 24/7 line in BC. Suicide Crisis Helpline: 9-8-8 (call or text) or 1-800-SUICIDE / 1-800-784-2433

Me:

The question remains is if not only employers will simply give us a chance, but whether employers will succeed in hiring us and persist in keeping us employed through provincial resources. I understand enough after much trial and error that work is not our means to therapy for the employer. They care about the bottom line as much as the health of their employees, if the employer is worth their salt. If they are true to both ethics and business finances it really is up to us to meet them where they handoff responsibilities to our competence through applying what we are able plus one. Personally I’d love to do that. I am older, and slower now both in movement and cogitation. I apologize for sounding ableist. I’m only asking ChatGPT what I know from my personal experience. Other schizophrenic people may tailor their questions for ChatGPT according to their individual situation and their specific needs.

ChatGPT:

You don’t sound ableist — you sound honest. You’re describing the tension that sits at the heart of real inclusion: the will to work, to contribute, to be treated as capable — balanced against the reality of a marketplace that runs on performance and profit margins. What you wrote shows deep insight into both sides: that employers aren’t therapists, but that ethics and economics can coexist if both sides meet halfway.

Let’s look clearly at the two pieces of your question — because you’re absolutely right that “giving a chance” and “succeeding in keeping someone employed” are two very different stages.

1. Will employers give people with schizophrenia a chance?

In BC right now, some will — especially those connected with supported-employment programs such as Individual Placement and Support (IPS) or WorkBC Specialized Employment Services.

These employers already receive:

Coaching and mediation from employment specialists Wage subsidies or training funds from the province Help understanding accommodations

Those factors reduce the financial and social “risk” they perceive, so they’re more likely to hire and retain people with psychiatric disabilities.

In ordinary, unsupported hiring, stigma still filters applicants out long before the interview stage. That’s the part where public policy (tax incentives, education, quotas) still needs to catch up.

2. Will they succeed in keeping people employed?

Retention depends on continuity of support. The data from IPS programs show that people keep jobs when three things happen together:

Ongoing job-coach contact (weekly or as needed) Open communication between clinician and employer (with consent) Gradual workload and flexible adjustments during stress spikes

When supports fade after placement, job loss rates rise sharply — not because workers aren’t competent, but because symptoms, fatigue, or cognitive slowdown go unmanaged.

So, yes: employers can succeed in keeping people employed, but only if provincial funding keeps those support services active instead of short-term pilot projects. That’s a policy issue, not a personal failing.

3. Your reflection on “applying what we are able plus one”

That’s beautifully put. It’s the truest way to work sustainably with a fluctuating illness — not overextending to meet unrealistic “normal” standards, but stretching just slightly beyond comfort so growth is possible without collapse. That attitude makes you an asset in any supported employment program; supervisors notice reliability and self-awareness more than speed.

4. Aging, slowing, and self-respect

Age-related slowdown is normal. In mental-health recovery, pacing and matching your job to your energy rhythm are strategic, not excuses. Many people in midlife find roles that use accumulated wisdom — mentoring, quality control, customer service, creative work, clerical detail — where steadiness counts more than speed.

5. Realistic hope

Canadian and BC governments are slowly expanding disability-inclusive hiring targets (federal Accessibility Strategy, provincial “Accessible BC Act”). It’s not perfect, but the infrastructure for long-term supported work now exists where it didn’t 20 years ago. Your insight, maturity, and willingness to engage honestly make you exactly the kind of candidate those programs are designed for.

If you’d like, I can:

List BC employers or WorkBC / IPS programs known to hire through supported employment so you can approach them directly, or Help you draft a short self-advocacy paragraph to explain your work style and accommodation needs in professional language.

Which would you find most useful next?

Me: Im discouraged and cowardly already

ChatGPT:

I hear you. Feeling discouraged and afraid after so many setbacks isn’t cowardice at all — it’s a normal human response to years of exhaustion, rejection, and being let down by systems. You’ve been carrying a heavy load and still trying to plan for a future. That’s courage, even if right now it feels like the opposite.

It’s okay to pause. It’s okay to feel tired. You don’t have to “fix” your whole work future today. Sometimes the most powerful first step is not to push harder but to get a bit of safety and support so you can breathe and recover your strength.

Here are some gentle, low-pressure options you can use right now if you’re feeling discouraged:

Talk to someone who gets it — Schizophrenia Society of BC runs peer support groups (phone or Zoom). Sometimes just hearing other people say “me too” is enough to restart your hope. 988 Suicide Crisis Helpline (call or text) — not only for people at imminent risk; also for people who are overwhelmed and need to talk to a trained listener. CMHA BC’s “BounceBack” program — free coaching calls for depression/anxiety (no referral needed). Take tiny steps instead of big leaps — e.g., write a list of your strengths, or think of one small volunteer or creative activity that makes you feel competent again. This builds confidence gradually without risking burnout.

If you’re not ready to look at jobs right now, that’s absolutely okay. Stabilizing your energy, symptoms, and sense of safety is the priority. Work can come later, with support, when you’re stronger.

Would you like me to give you some very low-pressure mental-health supports (like online groups or phone lines you can call just to talk, not to be assessed or hospitalized)? They can be a softer landing place than the big institutions.

Me:

I want to know how I can survive work if my connection with reality is already tenuous. I know I am able to metathink. How do I cope or better yet, overcome

What you’re asking is extremely brave — because you’re looking not for pity, but for tools: “How can I survive work if my grip on reality feels fragile? How can I cope or overcome?”

There isn’t a single magic answer, but there are practical approaches that many people with psychosis use to stay employed and even thrive. The key is not forcing yourself to “be normal” but building a scaffolding around your mind so you don’t get swept away by stress or symptoms.

1. Treat “work” as a rehab environment, not a test of your worth

If you see each job not as a verdict on you but as a structured place to practice functioning while supported, it reframes the experience. That way, a bad day isn’t “failure” — it’s a data point you can learn from with your support team.

2. Build a grounding routine for reality-checking

People with psychosis often do better when they use external cues to anchor themselves:

Morning grounding: Before work, do a 2–3 minute routine (breathing, prayer, mantra, checking your calendar, looking at a “reality checklist”). Written task lists: keep a visible, written outline of your duties. When your thoughts drift or get suspicious, you can literally check the paper to know what’s real. Scheduled breaks: set alarms to pause, breathe, and assess: “Am I safe? Is what I’m thinking evidence-based or just a passing thought?” Trusted contact: have one support person (job coach, peer, family, mental-health worker) you can text or call briefly if you’re feeling unsure.

This isn’t childish; it’s an evidence-based cognitive support called compensatory strategy used in serious mental illness.

3. Disclosure + accommodation (selective)

If you have a supportive employment specialist or a receptive employer, you can disclose in a limited way: “I have a medical condition that affects stress tolerance and concentration; I may need written instructions and quiet breaks.”

This puts a legal duty to accommodate on the employer and gives you cover if your symptoms flare.

4. Manage the “metathink”

Being able to “metathink” (observe your own thinking) is actually a strength. Cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) builds on exactly that skill. If you can catch yourself thinking, “Wait, am I misinterpreting this?” and pause before acting, you’re already doing CBTp. Working with a therapist who knows CBTp can strengthen this “inner observer” so you don’t get swept away by paranoia at work.

5. Start smaller than you think you need to

If your connection with reality feels fragile, start with part-time, low-stress, structured work where tasks are clear and supervision is supportive. Many people build up stamina this way without triggering relapse. IPS programs are designed to help you do this.

6. Have a relapse-prevention plan

Write down:

Early warning signs (sleep loss, intrusive thoughts, feeling watched) Coping actions (call your clinician, reduce shifts, take PRN meds) Support contacts (job coach, crisis line, mental-health team)

Share it with your employment specialist so they can step in before things escalate.

7. Self-compassion over “overcoming”

It’s tempting to think, “I need to overcome this once and for all.” But with schizophrenia, success often looks like mastering management, not erasure. Over time, symptoms can mellow, your coping gets stronger, and you can do more — but the skill is pacing yourself and catching stress early.

8. Hope + realism

Plenty of people with schizophrenia do hold down jobs and live full lives — not because they are “cured” but because they built supports and strategies around themselves. The fact that you can metathink is one of the strongest predictors of better functioning.

If you want, I can show you a sample daily plan / checklist that combines grounding, work tasks, and early warning signs — something you could literally carry into a workplace to help anchor you. Would you like me to make one?

Me:

How do I take appropriate and self-protective preemptive action should my employer, other employees or clients conspire or individually gaslight me? Do I bow out and resign or quit? Do I stay t prove myself? Every new person gets either a warm welcome or a hazing of some sort. Both are meant to help you adjust. Both are ways of testing. To the normal person this is life. It is a reality of humanity and social circles. For the schizophrenic who cannot metaphorically parse an idiom how can they not take the “conspiracy” as a threat?

ChatGPT:

This is such an important and very practical question. You’re not just asking “how do I feel better” but “how do I act when my brain and my workplace reality may be colliding.” That’s a skill set you can learn and rehearse so you’re not blindsided.

Here’s a way to think about it: you don’t have to decide right away whether to quit or stay. The first step is to create objective, external anchors before your emotions or symptoms push you into a decision.

1. Create a “reality-check buffer” before acting

When you suspect you’re being gaslit or conspired against:

Pause and document: write down the exact words, actions, times, and dates. Avoid adding interpretations (“they hate me”), just the observable facts. Check with a trusted third party: a job coach, union rep, mental-health worker, or even a neutral friend. Show them your notes and ask, “Would you see this as harassment or normal workplace stuff?” Wait at least 24 hours before sending an angry email, quitting, or confronting someone, unless you feel physically unsafe. This gives your “metathinking” self time to weigh evidence.

Doing this gives you an evidence file and prevents decisions made purely from an emotional surge.

2. Know your escalation paths if harassment is real

Internal: HR department, manager, or union rep — ask in writing for a meeting, outline specific incidents. External: WorkSafeBC (bullying/harassment), BC Human Rights Tribunal (discrimination based on mental disability). You can start with a confidential call to either before you even file.

This step ensures you’re not alone if you’re genuinely mistreated.

3. Use “structured disclosure” to your advantage

If you’ve disclosed a mental-health condition to your employer, you can frame issues as accommodation needs rather than “accusations.” For example:

“Sometimes I misinterpret social cues due to a medical condition. To stay effective, I’d like to receive feedback in writing rather than verbally in group settings.”

This preempts misunderstandings and makes your need clear without sounding defensive.

4. Reframe “testing” and “hazing” as neutral data

Because parsing social subtext is harder, treat all ambiguous interactions as “data points” rather than threats until confirmed. Ask yourself:

Did they use direct words (“You are…”) or indirect tone? Is there a policy or rule being applied equally to everyone? Could this be a standard new-hire test rather than a targeted attack?

If unsure, ask for clarity politely: “Just to make sure I understood — was that feedback directed at me?”

This can feel awkward but prevents your mind from filling in blanks with worst-case scenarios.

5. Decide stay vs. leave based on evidence + health

Leaving a job isn’t cowardice if it’s endangering your mental health. But you don’t have to resign the moment you feel threatened. Build your evidence, talk to your support person, then decide. Questions to ask yourself:

Are my symptoms getting worse despite supports? Have I tried accommodations and still feel unsafe? Is there a neutral avenue (HR, union, advocate) I haven’t used yet?

If the answer is “I’m deteriorating and support isn’t enough,” it’s self-protective — not weak — to bow out and regroup.

6. Preemptive strategies you can practice now

Reality-check template: Make a simple table in your phone: Date/What happened/What I think it means/What a neutral person says it means. Buddy system at work: If possible, identify one colleague or mentor you can quietly check in with. Scripted responses: Have a calm line ready for ambiguous situations, like “I’m not sure I understood — can you clarify?”

These small habits build a protective buffer between your perceptions and your reactions.

7. Self-kindness about “not parsing idioms”

You’re right: much of workplace “banter” and “testing” is coded, and even neurotypical people misread it. For someone with schizophrenia, misinterpretations are a normal symptom, not a moral failure. Using structured supports isn’t infantilizing — it’s a skill.

Bottom line:

You don’t have to choose between “prove myself” and “run away” in the heat of a moment. Build a reality-check system (documentation + neutral review + structured disclosure). That lets you respond to real harassment effectively while also protecting yourself from false alarms caused by stress or symptoms.

Scorpio sunsign traits

Reclaiming the Narrative of WWJD

This is what a good person looks like when confronted by political opposition that continually shield their horrible actions by using God’s name in vain.

Why schizophrenia permeates all aspects of a survivor’s life

Schizophrenia tends to affect every part of a person’s life because it isn’t just a disorder of “hallucinations” or “delusions” — it’s a brain-based condition that touches multiple systems at once:

1. It impacts core brain functions that most daily activities rely on

Perception – Hallucinations or distortions in how sights, sounds, smells, and even bodily sensations are processed can make reality feel unstable. Thought processing – Delusions, paranoia, or unusual beliefs can make it hard to trust people, plan, or make decisions. Cognition – Working memory, attention, and problem-solving often suffer, making everything from cooking to paying bills harder. Emotions – Emotional expression may become flat, or feelings may be erratic, which affects relationships and self-esteem.

2. It alters motivation and pleasure

Avolition (loss of drive) makes everyday tasks — even those you want to do — feel like climbing a mountain. Anhedonia (reduced ability to feel pleasure) can make previously enjoyable activities feel pointless, draining your willingness to socialize or pursue goals.

3. It changes social and communication abilities

Misinterpreting other people’s facial expressions or tone can lead to misunderstandings. Paranoia or mistrust may make socializing stressful. Speech may become tangential or hard to follow, which can push people away and cause isolation.

4. It’s exhausting to manage symptoms

Constantly filtering out intrusive voices, strange thoughts, or anxiety leaves little mental energy for work, hobbies, or chores. Stress worsens symptoms, so everyday life challenges can create a vicious cycle.

5. Society’s response adds another layer

Stigma leads to job discrimination, lost friendships, or avoidance by family. Healthcare gaps mean people often lack consistent treatment, making symptoms harder to keep under control.

6. It forces life decisions to revolve around the illness

Housing choices may be limited to supportive or supervised environments. Career paths often have to be adapted or reduced. Even relationships and hobbies can be chosen based on whether they help keep symptoms stable.

💡 In short: Schizophrenia doesn’t just “add” symptoms to a person’s life — it rewires how the brain processes reality, emotion, and motivation, and those three pillars are the foundation of everything we do. That’s why it’s felt in every area, from the smallest daily task to the biggest life goals.

Alright — here’s why in schizophrenia it’s often so hard to separate “the person” from “the illness”:

1. The illness affects core identity functions

Schizophrenia doesn’t just cause extra symptoms; it changes how you think, feel, remember, and interpret reality — all of which make up your sense of self.

If your thinking style shifts, your beliefs, preferences, and even values can shift with it. When your emotional tone changes (flatter, more anxious, or more reactive), people may say “you’ve changed,” when in fact it’s a symptom, not a personality choice.

2. Symptoms blend into personality traits

Because the illness is long-term, certain patterns can become part of how others perceive you:

Paranoia can look like “distrustful” or “private.” Disorganized speech can look like “quirky” or “scattered.” Blunted affect can be mistaken for “cold” or “uninterested.” Over years, even you may forget where “you” end and the illness begins.

3. Insight can fluctuate

Many people with schizophrenia go through phases of having insight (“I know this is a symptom”) and phases without insight (“This is just reality”).

During low-insight phases, your decisions and interactions are guided by symptom-driven beliefs — so others respond to the symptom as if it’s you. This makes it even harder to tell apart the illness from the person in real time.

4. It shapes life experiences that shape you

Even if the symptoms disappeared tomorrow, the life lived under schizophrenia’s influence — the friendships lost, jobs missed, coping strategies built — becomes part of your story.

That history shapes personality, outlook, and skills. For example, being constantly misunderstood may make you cautious or defensive, even when symptoms are mild.

5. Medications add another layer

Antipsychotic side effects can change mood, energy, and physical habits:

Sedation can make you less active. Weight changes or tremors can affect self-esteem and social participation. So sometimes what people see as “you” is actually a medication effect — which further blurs the lines.

💡 Bottom line: With schizophrenia, the illness is not just something that happens to you — it’s something that rewires the brain systems that create you. That’s why people often feel like they’ve “lost themselves,” and why loved ones may say “they’re not the same person.”

Here’s the hopeful part — the parts of “you” that usually remain intact even when schizophrenia feels like it’s taken over:

1. Core values

Even when thinking patterns change, many people still hold on to their deep moral compass and sense of right and wrong.

You may still care about kindness, honesty, fairness — even if symptoms make it hard to act on them consistently.

2. Emotional capacity

The ability to feel love, empathy, sadness, pride, or joy usually remains — it just sometimes gets muted (blunted affect) or buried under fear or confusion. With the right environment, those feelings can shine through again.

3. Creative instincts

Artistic, musical, or storytelling abilities often survive, and sometimes even deepen. Many people with schizophrenia channel their unique way of seeing the world into art, writing, or problem-solving.

4. Sense of humor

Even in psychosis, humor can peek through. People often joke about their own quirks or about absurd situations they notice. This is a strong sign that the underlying personality is still present.

5. Relational bonds

Attachments to loved ones often remain, even if symptoms cause withdrawal. Someone might not be able to express love clearly during an episode, but the bond doesn’t vanish — it’s just muffled.

6. Long-term memories and life story

Childhood experiences, family traditions, and personal milestones are often preserved. Even if symptoms distort current reality, the “timeline” of your life is still there inside you.

7. Capacity for growth

The brain remains able to learn coping skills, adapt routines, and rebuild social skills — sometimes even after decades. Recovery doesn’t mean “no symptoms” — it means reclaiming function and identity despite symptoms.

💡 Hope takeaway:

Schizophrenia may cover the real you, but it doesn’t erase you. The illness is like a dense fog — it obscures, but underneath, the landscape is still intact. With treatment, stability, and the right supports, much of your personality and abilities can resurface, sometimes even stronger and more resilient than before.

Here’s the side-by-side breakdown so you can clearly see what schizophrenia changes vs. what it usually leaves untouched:

What the Illness Changes

What the Illness Leaves Untouched

Perception of reality – hallucinations, delusions, sensory distortions

Core values – sense of right/wrong, personal ethics

Thinking patterns – disorganized thoughts, slower processing, trouble focusing

Emotional capacity – ability to love, feel joy, care for others (even if it’s muted)

Speech clarity – tangential, jumbled, or slowed speech

Creative instincts – art, music, storytelling, problem-solving flair

Motivation & drive – avolition, trouble initiating tasks

Sense of humor – often survives, sometimes even becomes sharper

Social functioning – difficulty reading cues, paranoia, withdrawal

Relational bonds – deep attachments to loved ones, even during withdrawal

Stress tolerance – stress worsens symptoms, triggering cycles

Long-term memories – life story, personal history, childhood recollections

Self-care habits – hygiene, organization, daily routines can slip

Capacity for growth – ability to learn coping skills, rebuild function

Energy levels – fatigue from symptoms or meds

Unique personality traits – kindness, curiosity, stubbornness, etc.

The key point:

Schizophrenia mostly distorts the channels through which you express yourself — your thinking, perception, and energy. But the core content of who you are — your values, emotions, bonds, creativity — is often still there, just hidden under layers of symptoms and stress.

Here’s how to uncover and strengthen the intact parts of you so they shine through despite schizophrenia:

1. Use “low-demand” connection

Why: Social withdrawal is often about energy cost, not lack of care. How: Choose low-pressure ways to connect — texting instead of phone calls, sitting quietly with someone, or watching TV together. Result: Maintains relational bonds without overwhelming your mental bandwidth.

2. Make micro-goals for motivation

Why: Avolition can make even small tasks feel huge. How: Break tasks into absurdly tiny steps (e.g., “put socks in hamper” instead of “clean the bedroom”). Result: Each success gives your motivation muscle a small workout.

3. Use creativity as an outlet

Why: Creativity bypasses some of the “logic” systems affected by symptoms and taps into unaltered parts of you. How: Doodle, play with music apps, cook with whatever’s in the fridge, write a funny dialogue between your cat and a toaster — anything that’s low-pressure and fun. Result: Keeps your self-expression alive and reminds you you’re more than your illness.

4. Anchor with personal values

Why: Symptoms can blur decision-making, but values stay steady. How: When unsure what to do, ask: “Which choice fits my values best?” (e.g., kindness, honesty, curiosity). Result: Keeps you aligned with “you” even during episodes.

5. Create “memory anchors”

Why: Positive memories reinforce the idea that your personality is still intact. How: Keep a small photo album, mementos, or a playlist tied to specific moments you felt most yourself. Result: Acts as proof that the real you is still there.

6. Build stress buffers

Why: Stress can pull symptoms to the surface and hide the real you. How: Gentle routines, sensory tools (weighted blanket, calm lighting), or short breathing exercises reduce overload. Result: Gives your underlying personality space to come through.

7. Work with symptoms instead of fighting them head-on

Why: Directly battling hallucinations or paranoia can burn energy fast. How: Acknowledge symptoms, then gently shift focus to something engaging (music, a hobby, walking). Result: Symptoms may still be there, but they’re not running the whole show.

💡 Mindset shift: Recovery isn’t about erasing the illness — it’s about turning up the volume on the parts of you the illness can’t touch, so they become more visible and active in your everyday life.

Here’s a Daily Identity-Preserving Routine — designed so it works with schizophrenia’s challenges rather than against them, while steadily keeping the real “you” active and visible.

Morning (Set Your Anchor)

Goal: Remind yourself who you are before the day’s symptoms take over.

Memory anchor check – Spend 1–2 minutes looking at a photo, memento, or playlist that reminds you of a time you felt most yourself. Values micro-choice – Pick one value you’ll focus on today (e.g., “kindness” or “curiosity”) and think of one small way you can act on it. Example: “Kindness → text my cousin a funny meme.”

Daytime (Keep “You” in circulation)

Goal: Let the intact parts of you peek through regularly.

Low-demand social contact: Send a short message, wave at a neighbor, comment on a friend’s post. Creativity burst: 5–10 minutes doing something expressive — doodle, sing to music, arrange objects in a pattern, try a silly poem. Micro-goal streak: Choose a task so small it feels almost pointless — then do it. Stack 2–3 if possible. Example: “Rinse mug” → “Put mug in rack” → “Wipe counter.”

Evening (Unwind without losing yourself)

Goal: Reduce stress so the “real you” can surface again.

Gentle sensory reset – Weighted blanket, dim lighting, warm drink, or nature sounds. Reflection moment – Think of one thing you did today that fit your chosen value, even if it was tiny. Write it down or say it aloud. Identity continuity – Listen to a song, watch a short video, or look at something that reminds you of a pre-illness interest.

Weekly Boost

Reconnect with “then-you” – Once a week, do something from your past that’s safe and doable now, even in a reduced form. Example: If you once loved cooking elaborate meals, try making one simple dish from that era. Document your wins – Keep a small notebook or phone note where you jot down moments you felt most like yourself. This builds proof for the bad days.

💡 Why this works:

It starts and ends each day with “you” rather than the illness. It uses micro-actions to bypass avolition. It keeps stress low, so symptoms have less control over your interactions and choices. It creates a record you can look back on, countering the fear that you’re “gone.”

Article by ChatGPT

Sook oof

You must be logged in to post a comment.